China may be halting construction of coal-fired power at home but abroad it’s still investing in coal, even as it pushes aggressively into renewable energy markets.

In the years ahead, the kind of investments China makes in Turkey will prove an important test of its emerging leadership on energy and climate.

China has strengthened its bilateral relationship with Turkey in recent years. Chinese wind power companies MingYang and Goldwind were among eight international consortia that took part in a tender for a one gigawatt wind project in July, organised by the Turkish Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources.

Despite Turkey’s on-going national state of emergency and political instability following a coup attempt in July 2016, companies, including those from China, have not been put off bidding for a stake in Turkey’s future energy infrastructure.

Securing overseas energy contracts is now a top priority for President Erdoğan’s government, which hopes to mend Turkey’s budget deficit by reducing dependence on energy imports. To do this it wants to fully utilise domestic energy resources such as wind and solar, but also coal.

The announcement of the winning tender in Istanbul, by Siemens and the Turkish conglomerates Türkerler and Kalyon, was followed by extreme rainfall. Although the downpour came just ten days after another extreme precipitation event, city officials and residents were caught off-guard. The high wind speeds toppled a crane at the Haydarpaşa port, which crashed into an oil tanker resulting in a fire and explosion.

The accident was a reminder that extreme weather events are expected to become more intense and frequent globally, marking a “new normal” in Turkey. As climate change is caused by burning carbon, China can either adversely contribute to this pattern by investing in coal power or use its energy investments to steer the country in a more sustainable direction.

Actions speak louder than words

In early July, the much-acclaimed Paris Agreement appeared to pass the “Trump stress test” when 19 of the 20 G20 members (including Turkey and China) endorsed the Hamburg Climate and Energy Action Plan for Growth, a joint strategy to pursue climate goals set out in the Paris Agreement.

But away from the high level meetings, the Turkish government’s actions on climate and energy were telling.

During a press meeting following the G20, President Erdoğan made it clear that Turkey would not ratify the Paris Agreement until its demands on technology transfers and access to climate finance were met.

On July 9, the day after the G20 summit closed, Erdoğan addressed the leaders of the global oil industry at the 22nd World Petroleum Congress held in Istanbul. This major event was also accompanied by extreme weather in Turkey, in this case a heatwave.

In his speech to the oil industry leaders, Erdoğan stated that demand for global energy is expected to double by 2050 and that Turkey’s primary objective is to fully tap into domestic energy sources, including its low quality coal reserves, while continuing to import fossil fuels.

Chinese investment is key to making this happen.

Closer ties

Since assuming his position in late 2015, Turkish Minister of Energy and Natural Resources and Erdoğan’s son-in-law, Berat Albayrak, has paid several visits to China to push for greater energy investment in Turkey. In March 2016, Albayrak and the head of China’s National Energy Administration, Nur Bekri, met to discuss new cooperation opportunities in energy. During this visit, Albayrak also met with some of China’s coal industry giants.

The recent newsletter of the Turkish Exporters Assembly suggests that Turkey “aims to establish a proper legal infrastructure, lift all trade barriers, [and] develop an effective cooperation in the field of customs and standards” with China.

The interest is mutual. Chinese firms are keen to participate in the Turkish energy market, particularly following the country’s long-awaited “centres of attraction” programme, announced in a state-of-emergency decree in November 2016.

The programme seeks to incentivise new investments through interest-free credit and low-interest working capital loans, and covers 23 provinces in the eastern and south-eastern Anatolian regions that face regional economic disparities. So far, 53 Chinese companies – 39 of which are new players in the Turkish market – have applied to the Ministry of Development for permits to take part.

Closer engagement on energy

Despite occasional setbacks, Turkey and China have undoubtedly been developing closer economic ties. Several bilateral agreements were signed between 2010-2012, helping trade to grow, although largely in China’s favour. The number of high-level visits and business delegations has increased accordingly.

In 2015, Turkey’s total exports to China were US$2.4 billion (15.8 billion yuan) just a tenth of China’s exports to Turkey, which totalled US$24.9 billion (164 billion yuan).

Erdoğan has referred to this uneven trade balance, underlining his desire to see further direct Chinese investments. Turkey and China’s successive G20 presidencies in 2015 and 2016 also helped redress the balance, and today China is Turkey’s second largest trade partner globally after Germany, and principal trade partner in East Asia.

Turkey wants to attract energy investment quickly and China is looking to shift excess capital and production capacity, particularly in the power sector and as part of its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

Erdoğan’s personal visits to China in 2015 and 2017 have stimulated action, and followed a number of deals signed in 2012. One of these included Hattat Holding and China’s AVIC International signing an agreement worth US$1.5 billion (10 billion yuan) for the construction of a coal-fired power station in the Amasra region, a key site of popular dissent against coal projects.

Another involved Ağaoğlu construction group, which is known for its close ties with the Turkish government, reaching an agreement with China’s wind turbine maker Sinovel for a 600-megawatt installation, valued at US$1 billion (6.6 billion yuan).

Both the former energy minister Taner Yıldız, and current minister, Berat Albayrak have made deals on energy investment and technical cooperation, particularly in areas of nuclear and thermal power generation. During one of his recent visits, minister Albayrak stated that Turkey needed to expand installed power capacity by at least 50 gigawatts over the next decade, which would require an investment of US$100 billion (659 billion yuan).

These efforts were crowned by new deals on nuclear cooperation and an agreement of exclusivity with the Chinese State Nuclear Power Technology Corporation (SNPTC) for construction of a third nuclear plant in Turkey with an installed capacity of five gigawatts.

Additionally, Turkish and Chinese companies signed new commercial deals on coal mining, hydropower projects and high-speed railway lines, bringing Chinese foreign direct investment (FDI) in Turkey to US$642.3 million (4.2 billion yuan) in 2016.

Turkey’s push to maximise use of domestic coal undermines its ability to reduce carbon emissions. Furthermore, the country’s commitment under the Paris Climate Agreement does not include a target to reduce absolute emissions or even to peak them around the 2030s.

Indeed, Turkey’s emissions may double by 2030 compared with 2012. This has led Climate Action Tracker, an independent research group, to rate Turkey’s plans as “inadequate”.

China’s coal investments in Turkey

The early ratification of the Paris Agreement has put coal – the single most polluting energy source – firmly on the global energy agenda. Limiting export credits and ceasing public finance for coal-fired power generation are key issues for multilateral and international financing institutions.

One recent study found that China accounted for 40% of public financing for coal projects between 2007-2013 and is likely to compensate for international public finance cuts on coal by OECD members. China channels vast amounts of public finance to overseas coal investments, particularly through the China Development Bank, Export-Import Bank of China, and SINOSURE. These resources also prop-up China’s state-owned thermal power sector giants such as Harbin Electric, Dongfang Electric, and Shanghai Electric.

China’s trade surplus, excess production capacity and social-environmental pressures pushed the country to restructure its economy and the energy system. China’s “going-out” strategy adopted in 2001 encouraged Chinese FDI to reach US$118 billion in 2015. According to a recent study, introduction of the BRI in 2013 significantly shifted public finance flows towards BRI-partner countries.

It is striking that in 2015 alone, the amount of new foreign construction project contracts signed between China and BRI countries reached a record high of US$92.6 billion (610 billion yuan).

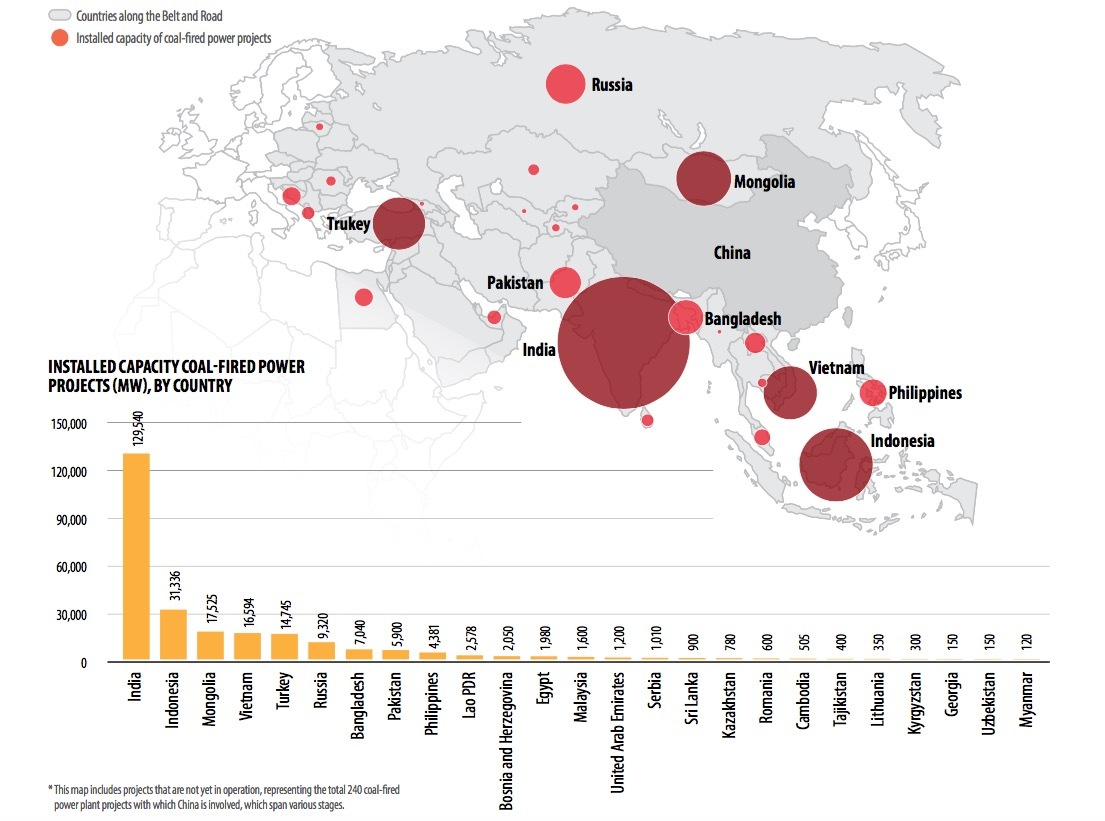

Energy projects, particularly coal-fired power plants have been the main focus. According to another study, by the end of 2016, China was involved in 240 coal-fired power projects in 25 of the 65 BRI countries, with a total installed capacity of 251 gigawatts.

Coal fired power plant projects with Chinese involvement in BRI-partner countries. Source: GEI, 2017

Foreign direct investment to the Turkish power sector has been rising for more than a decade due to favourable economic conditions and political support.

In fact, for many developing countries like Turkey, Chinese coal financing terms offer significant cost advantages over the large multilateral development banks and international financial institutions.

However, tracking Chinese financing in Turkey’s coal projects is challenging because most Chinese institutions do not reveal such information openly. Lack of democratic accountability looms large in many energy projects with bilateral financing.

Still, there are exceptions.

Hunutlu coal-fired power plant is one such case.

Located in the city of Adana, southern Turkey, it received construction permission in 2015. The funder Emba Elektrik Üretim AŞ is a Turkish-Chinese joint venture of Shanghai Electric Power Co Ltd, Avic-International Project Engineering Company, and four undisclosed Turkish investors. While Shanghai Electric Power holds 50.01% of the shares, AVIC-International holds 2.99%, with the Turkish investors accounting for the remaining 47%.

A key concern is how this bilateral deal is being used to bypass stringent social and environmental assessments, which have proven to be grounds for opposition to other similar projects.

The Turkish government has been keen on using intergovernmental agreements (such as in the case of the Akkuyu Nuclear Power Plant agreement with Russia) instead of trade deals that are easily terminable. This casts the deals in stone because Turkey ceases its territorial sovereignty for a certain time period meaning that environmental legislation is not fully and transparently enforceable.

Outlook

Chinese companies have announced intentions to build or operate at least 92 new coal-fired power plants across 27 countries, including three in Turkey at Amasra, Adana Hunutlu and Konya Ilgın. The majority of these power plants (58%) use sub-critical technology, meaning they are less efficient.

So while China is halting new coal plant projects at home, envisaging peak emissions and boosting renewable-based power generation, it is continuing to shift environmental costs and maintain the economic benefits of pursuing aggressive overseas coal investment, with Chinese companies in BRI countries backed by state finance.

Although China is leading the world in solar energy deployment, generous Chinese public finance for fossil-fuel driven energy projects may add fuel to the fire of authoritarian developmentalism in countries like Turkey.

Turkey’s rapidly changing foreign policy means it is likely to become increasingly reliant on Chinese energy financing, including for additional coal investments. Furthermore, as Turkey faces major roadblocks in the European Union accession process resulting from the deterioration of democracy and rule of law in the country, the pressure on Turkish companies to act in accordance with stringent environmental and social policies is likely to diminish.

Public debate over linkages between climate and energy is returning to the centre of political attention. There is a parallel between the dissent in China caused by poor air quality and the threat to livelihoods and people’s health in Turkey arising from polluting energy and mining projects.

There is great potential for China to demonstrate its climate leadership by steering Turkey in the direction of a clean energy system through its investments. The question is whether China will ignore its coal interests and encourage Turkey to pursue options beyond fossil fuels that are needed to secure a just and low carbon future.

![View of Pul Doda from the road above, a half submerged structures of a mosque, a temple and a few houses can be seen [image by: Majod Maqbool]](https://dialogue.earth/content/uploads/2017/10/A-view-of-the-Pul-Doda-area-from-the-road-above.-The-half-submerged-structures-of-a-mosque-a-temple-and-a-few-houses-can-be-seen-here.-300x184.jpg)