Sanchi, the Panama-registered oil tanker that set fire after colliding with a Hong Kong freighter on January 6, sank at about 5pm on Sunday, according to a report by China Science Daily. CCTV reported that flames at the location where the vessel sank went out the following morning.

Rescuers have retrieved the bodies of three Sanchi crew members but 29 remain unaccounted for. The collision of the Iranian-owned tanker with the Chinese freighter CF Crystal took place 160 nautical miles east of Shanghai.

Environmental impacts

It’s still too early to know how the oil spill will affect wildlife and the marine environment but long-term monitoring will be needed to understand this. The damage from oil spills is difficult to gauge because there are so many factors at play: the type of oil leaked, the direction of ocean currents, weather conditions and the environment where the leak took place are all important.

The Sanchi was transporting 136,000 tonnes of condensate from Iran to South Korea when the collision happened. There is still no firm data on the volume of spilled oil, but the oil slick is reported to be 10 nautical miles long and 1-4 nautical miles wide. Two Chinese vessels are reported to be cleaning up the slick with foam detergents, while the State Oceanic Administration’s East China Sea bureau is using radar to measure its extent and impact.

Oil spills are usually associated with crude oil – a sticky black or dark brown liquid – but condensates are quite different. They exist in gaseous form in high-pressure oil reservoirs but condense into liquids when extracted. Condensates are easily refined into high-value oil products such as petroleum, diesel, aviation fuel and heating fuel, and are referred to as “the champagne of crude oil”.

Condensates are less toxic than crude oil and slightly soluble in water. They also evaporate more easily and are more flammable, which explains why the Sanchi burned for several days after the collision.

Because the collision took place over 100 nautical miles offshore, the impact on the marine environment and nearby fisheries may be lessened although south-flowing ocean currents could carry pollution to the Zhoushan fisheries off China's east coast.

An official with the East China Sea office of the State Oceanic Administration, which is responsible for monitoring the marine environment and responding to emergencies, said in an interview with Caixin on January 11 that the latest monitoring data obtained by the coastguard showed “no oil blooms, low oil concentrations, and water quality within Category I standards” between 1.3 and 19 nautical miles from the Sanchi.

The administration also told media last week that the weather conditions and location of the Sanchi meant, “the accident will not currently have any impact on the coastal environment.” Modelling by the Yantai Oil Leak Response Centre suggests that only 1% of condensates remain in the water five hours after a leak.

The distance from shore can make a big difference to the environmental damage from oil spills. For example, when the Atlantic Empress oil tanker sank following a collision in 1979 it spilled 280,000 tonnes of oil – the largest ever release from a tanker. However, the oil did not reach the coast, which lessened the damage. In contrast, the 1989 Exxon Valdez spill in Alaska was smaller but devastated 1,300 miles of coastline in the Prince William Sound, killing much of the local wildlife.

Can spills be stopped?

There will always be a risk of marine oil leaks although it is possible to use legal, regulatory and technical measures to reduce their likelihood, ensure responsible parties are held to account, and deal with the consequences.

A year after the Exxon Valdez leak, the United States passed a law requiring new tankers working in US waters be double-hulled so that if a grounding or collision happened a leak would be less likely. In 1992 the International Marine Organisation followed-suit, requiring all new tankers to be double-hulled and for existing tankers to be raised to the same standard. The MARPOL convention is the most important international agreement designed to prevent marine pollution from shipping. China is an IMO member and MARPOL signatory.

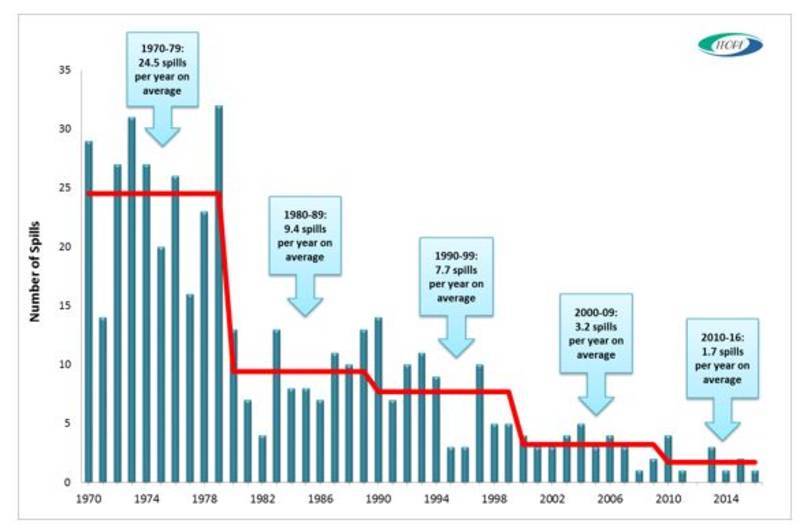

The double-hull standards and other changes have helped to reduce spills, which dropped significantly from the 1990s onwards.

Number of large and medium-sized oil spills over 700 tonnes, 1970-2016. Source: ITOPF

A number of details about the Sanchi, such as its age and whether it met safety standards are still unknown. What we do know is that the oil trade relies heavily on huge numbers of tankers travelling long distances through busy shipping lanes in changeable weather. Whilst this is the case, it will be impossible to completely prevent vessels from colliding or running aground.

While the oil trade has expanded since the 1980s, the number of oil spills has decreased. That’s good news, but it doesn’t mean we can stop worrying: there is still a need for quality, long-term research into the effects of oil spills on the marine environment and wildlife.