Restricting global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius could limit the most disastrous impacts of climate change, but doing so will require “rapid, far-reaching and unprecedented changes in all aspects of society,” according to a new scientific report commissioned by the United Nations.

For this, the world must reduce its carbon dioxide emissions by 45% by 2030 (from 2010 levels), and reach “net zero” by 2050, according to a study by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

This will require an annual average investment of around US$2.4 trillion (at 2010 prices) between 2016 and 2035, representing approximately 2.5% of global gross domestic product (GDP). The cost of inaction and delay, however, will be many times greater.

Global warming has already reached 1C with the effects evident in rising sea levels; and the greater frequency of heat waves, glacier retreat, coral reef deaths, severe storms, floods and droughts.

In December 2015, governments from around the world pledged in the Paris Agreement to limit warming to 2C, with the aspirational goal of a 1.5-degree limit. At that time, governments asked the IPCC – a collective of international scientists – to produce a report outlining the action needed to curb global temperatures at 1.5C above preindustrial levels.

This was the report the IPCC released on October 8, following a week-long fracas that saw the US and oil-export-dependent Saudi Arabia attack the findings of 97% of the world’s scientists, who agree that climate change is happening and is human caused. President Trump has already announced that the US will withdraw from the Paris Agreement. Last week, his bureaucrats tried their best to water down the report’s summary for policymakers. By and large, they failed. The battleground now shifts to Poland, which is hosting the next UN climate summit this December.

The IPCC report calculates that current national pledges, made under the Paris Agreement, will “result in a global warming of about 3C by 2100, with warming continuing afterwards. Avoiding overshoot and reliance on future large-scale deployment of carbon dioxide removal can only be achieved if global CO2 (carbon dioxide) emissions start to decline well before 2030.”

The findings

“One of the key messages that comes out very strongly from this report is that we are already seeing the consequences of 1C of global warming through more extreme weather, rising sea levels and diminishing Arctic sea ice, among other changes,” said Panmao Zhai, co-chair of IPCC Working Group I, which assesses the physical science basis of climate change. Zhai heads the Chinese Meteorological Society and is associated with the Chinese Academy of Meteorological Sciences, Nanjing and Lanzhou universities.

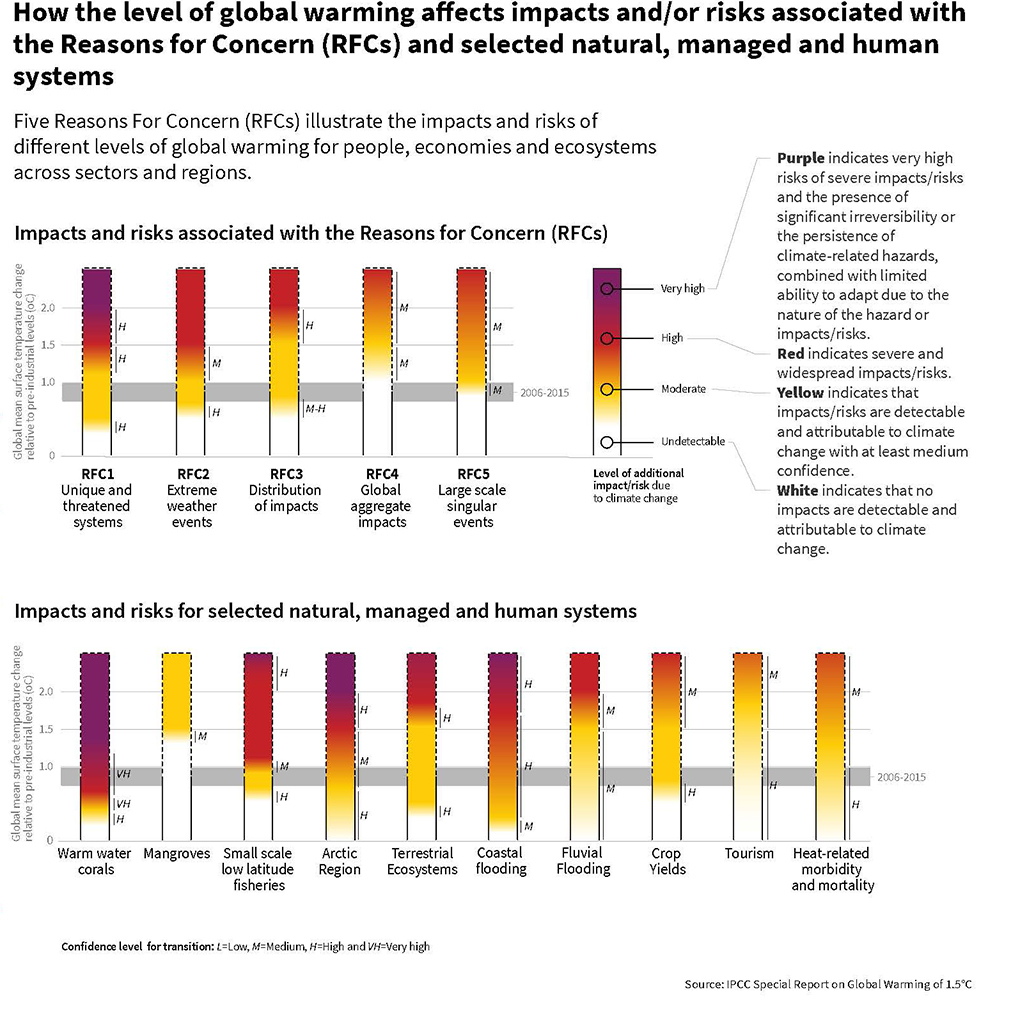

There are many benefits to limiting warming to 1.5 degrees: sea level rise would be 10 centimetres lower compared to a 2C scenario; summer sea melt the Arctic would happen once per century, compared to at least once per decade; coral reefs would still decline by 70-90%, but they would decline by over 99% if temperature rise reached 2C.

“Every extra bit of warming matters, as warming of 1.5C or higher increases the risk associated with long-lasting or irreversible changes, such as the loss of some ecosystems,” said Hans-Otto Pörtner, co-chair of IPCC Working Group II, which addresses climate change impacts, adaptation and vulnerability.

Limiting warming to 1.5C would require “rapid and far-reaching” transitions in land management, energy, industry, buildings, transport and cities, says the IPCC, balanced by removing CO2 from the air.

If temperature rise overshoots 1.5C even temporarily, the world will be more dependent on technologies to remove CO2 from the air to return to a 1.5C ceiling by 2100. These are unproven at large scale, and some may carry significant risks for sustainable development, the report notes.

“Limiting global warming to 1.5C compared with 2C would reduce challenging impacts on ecosystems, human health and well-being, making it easier to achieve the UN Sustainable Development Goals,” said Priyadarshi Shukla, co-chair of IPCC Working Group III, which deals with the mitigation of climate change. Shukla teaches at the Indian Institute of Management Ahmedabad and at Stanford University.

Likely impacts

Based on current rates, warming is likely to reach 1.5C between 2030 and 2052, according to the report. Estimated human-caused warming is increasing at 0.2C per decade due to past and on-going emissions of greenhouse gases, mainly carbon dioxide.

Past emissions alone are unlikely to warm the earth by 1.5C, so there is hope if countries take immediate action. There are two ways the world can reach the 1.5-degree ceiling by 2100; either by overshooting it followed by retrospective action, or by keeping within the ceiling. The first option is riskier: “Some impacts may be long-lasting or irreversible, such as the loss of some ecosystems.”

These irreversible impacts — or tipping points — include Antarctic and Greenland ice sheet melt, which could result in a multi-metre sea level rise over hundreds to thousands of years. These instabilities could be triggered around 1.5C to 2C of global warming.

Model-based projections of global mean sea level rise (relative to 1986 – 2005) suggest a range of 0.26 to 0.77 metres by 2100 for 1.5C global warming; 0.1 metres less than for a global warming of 2C. This reduction implies that up to 10 million fewer people would be exposed to related risks.

The human impacts

On land, the number of hot days is projected to increase in most regions, with the highest increases in the tropics, even if global temperature rise is kept within 1.5 degrees. Climate-related risks to health, livelihoods, food security, water supply, security and economic growth are all expected to rise with global warming.

Disadvantaged and vulnerable populations, some indigenous peoples, and agricultural and coastal livelihoods are at greater risk. Regions at disproportionately higher risk include Arctic ecosystems, dry land regions, small-island developing states and least developed countries. But sticking to the limit could reduce the number of people exposed to climate-related risks and poverty by several hundred million by 2050.

Limiting warming to 1.5C will mean smaller yield losses in maize, rice, wheat, and potentially other cereal crops, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, Southeast Asia, and Central and South America. The effect on the nutritional quality of rice and wheat will be the same.

Depending on future socioeconomic conditions, limiting global warming to 1.5C may reduce the proportion of the world population exposed to more water stress by up to 50%, although there is considerable variability between regions. Many small island developing states will experience lower water stress as a result of projected changes in aridity when global warming is limited to 1.5C.

Exposure to multiple and compound climate-related risks increases above that level, with more people susceptible to poverty in Africa and Asia. Risks to energy, food and water could overlap and worsen current hazards and vulnerabilities for increasing numbers of people and regions, warns the IPCC.

There will be less impact on biodiversity and ecosystems, too. Of 105,000 species studied, 9.6% of insects, 8% of plants and 4% of vertebrates are projected to lose over half of their geographic range at 1.5C, compared with 18% of insects, 16% of plants and 8% of vertebrates at 2C. Impacts associated with other biodiversity-related risks such as forest fires, and the spread of invasive species, are lower at 1.5C compared to 2C of global warming.

Keeping warming to 1.5C would also limit the rise in ocean temperature and acidity and the decrease in ocean oxygen levels. That will reduce risks to marine biodiversity, fisheries, and ecosystems, and their functions and services to humans, as shown by recent changes to Arctic sea ice and warm water coral reef ecosystems.

The experts have modelled various pathways to stick to the 1.5C ceiling. If it is not to be overshot, or overshot only by a limited extent, global net CO2 emissions by humans have to decline by about 45% from 2010 levels by 2030, reaching net zero around 2050. In contrast, for limiting global warming to below 2C, CO2 emissions are projected to decline by about 20% by 2030 in most pathways and reach net zero around 2075.

These 1.5C pathways also need deep cuts in emissions of methane and black carbon (35% or more of both by 2050 relative to 2010) and reduction in most cooling aerosols, which are potent greenhouse gases. The IPCC says, “Non-CO2 emissions can be reduced as a result of broad mitigation measures in the energy sector. In addition, targeted non-CO2 mitigation measures can reduce nitrous oxide and methane from agriculture, methane from the waste sector, some sources of black carbon, and hydrofluorocarbons.”

Improved air quality from reductions in many non-CO2 emissions provide direct and immediate health benefits, notes the report.

These pathways can be followed through different mitigation strategies, but all use carbon dioxide removal from the atmosphere to varying amounts, plus Bioenergy with Carbon Capture and Storage (BECCS) and removals in the Agriculture, Forestry and Other Land Use (AFOLU) sector, the IPCC says. What it does not say is that Carbon Capture and Storage remains a commercially unviable technology.

As expected, pathways that stick to the lower limit show more rapid and pronounced system changes over the next two decades. Renewables are projected to supply 70-85% of electricity in 2050. Shares of nuclear and fossil fuels with CCS are modelled to increase, allowing natural gas to generate about 8% of global electricity in 2050.

In these pathways, the use of coal falls almost to zero by 2050. This is bound to worry Indian policymakers, who are still talking about getting 45% of the country’s electricity from coal around the middle of the century.

In these pathways, CO2 emissions from industry are projected to be about 75–90% lower in 2050 relative to 2010. The IPCC says this can be achieved through combinations of new and existing technologies and practices, including electrification, hydrogen, sustainable bio-based feedstock, product substitution, and carbon capture, utilisation and storage. In industry, emissions reductions by energy and process efficiency by themselves are insufficient for limiting warming to 1.5C with no or limited overshoot, the experts warn.

These pathways would also need changes in land and urban planning practices, as well as deep emissions reductions in transport and buildings. In the transport sector, the share of low-emission final energy would rise from less than 5% in 2020 to about 35-65% in 2050.

One big problem with the IPCC pathways is that they project moving large tracts of land from raising food crops and livestock to biofuels. The experts are aware of the problem, and say, “Mitigation options limiting the demand for land include sustainable intensification of land use practices, ecosystem restoration and changes towards less resource-intensive diets.”

The report refers to the many advantages of adaptation to climate change impacts. “Adaptation options that reduce the vulnerability of human and natural systems have many synergies with sustainable development, if well managed, such as ensuring food and water security, reducing disaster risks, improving health conditions, maintaining ecosystem services and reducing poverty and inequality. Increasing investment in physical and social infrastructure is a key enabling condition to enhance the resilience and the adaptive capacities of societies.”

The IPCC adds, “Adaptation options that also mitigate emissions can provide synergies and cost savings in most sectors and system transitions, such as when land management reduces emissions and disaster risk, or when low carbon buildings are also designed for efficient cooling.”

Government policies that lower the risk of low-emission and adaptation investments can facilitate the mobilisation of private funds and enhance the effectiveness of other public policies, the report points out.

Overall, “The lower the emissions in 2030, the lower the challenge in limiting global warming to 1.5C after 2030 with no or limited overshoot. The challenges from delayed actions to reduce greenhouse gas emissions include the risk of cost escalation, lock-in in carbon-emitting infrastructure, stranded assets, and reduced flexibility in future response options in the medium to long-term,” the IPCC warns.

This story originally appeared on The Third Pole.