This week, the board of French state-controlled utility EDF postponed a vote on what would be the largest nuclear project in Europe in decades.

A thumbs-up from the directors would have prompted EDF to deepen cooperation with Chinese counterpart CGN in the Hinkley Point C project, a plan to build two European pressurised water reactors (EPRs) in Somerset, England. The estimated cost is £24.5 billion.

The delayed decision, along with the huge cost of the project and major doubts about the reactor design, has increased expectations that the power station will not go ahead.

The saga of the French project in the UK is symptomatic of the state of the world nuclear industry—one step forward, two steps back. Is it now less certain that China is the exception to the rule? In a surprise move the Chinese government just stopped the construction of two EPRs in Guangdong province due to safety concerns.

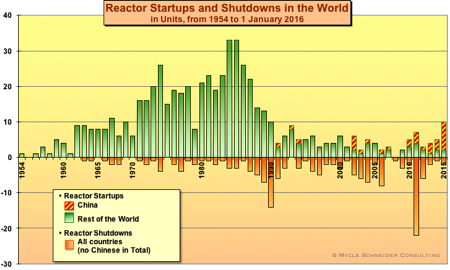

At first sight, 2015 was a good year for the world nuclear industry. A total of ten new nuclear reactors were connected to the grid, more than in any other year since 1990, while only two units were shut down, one in Germany and one in the UK. At the start of this year, a total of 398 reactors—eight more than a year ago—were operating in 31 countries.

Construction began on seven units. Two reactors were restarted in Japan, the first ones after the country’s nuclear fleet was shut down in the wake of the 2011 Tsunami and earthquake that prompted a meltdown at the Fukushima nuclear plant.

A framework investment agreement was signed between British, French and Chinese partners for the launch of a new power plant at Hinkley Point in the UK. And also last year, preparations for a call for tender for the construction of new nuclear plants were initiated in South Africa.

However, a closer look shows that the future potential for nuclear is mainly focused on China, whereas the situation of the nuclear industry in the rest of the world remains gloomy. Worse, less than two months after the signature of the Paris Agreement on climate change, the French nuclear industry is facing corporate meltdown.

See also: The global nuclear decline

Source: World Nuclear Industry Status Report (or simply WNISR), MSC, 2016

China represents eight out of the ten new reactors started up, and six of the seven new building sites. One reactor started up in South Korea, and another in Russia, after 31 years of construction. Japan confirmed the final closure of five reactors that had not generated power since the aftermath of the Fukushima accident.

Sweden decided to permanently close a unit that initially shut down in 2013 for upgrade work because the operator had calculated that it was no longer economically viable.

The Swedish move was not the first and certainly not the last utility decision to withdraw licensed reactors from the grid. “Things are tough for nuclear power at the moment”, head of generation at the Swedish utility Vattenfall, said last month.

“So far, a good many of our investments have been made in the hope that electricity prices will start to rise. But clearly there are fewer and fewer signs that this will actually happen. We don’t expect to see higher market prices for electricity over the next five or ten years.”

Vattenfall’s CEO Magnus Hall has added: “We are going through a paradigm shift, which is challenging the model of large-scale energy generation and distribution to end users in favour of decentralised and individualised energy solutions.” The company intends to spend SEK50 billion (US$5.9 billion) on renewables until 2020. At the same time, Vattenfall has announced that it will prematurely retire three additional reactors before 2020.

Consequently, nuclear new-build for Vattenfall is a non-starter. A similar situation is observed in other countries, particularly the US, where two reactors, licensed to operate into the 2030s, have been closed, while two more will be shut down until 2017, because they cannot compete in the power markets.

In effect, all of the nuclear new-build projects beyond the five reactors currently under construction have been delayed indefinitely. Outside China, only one construction site broke ground in 2015, in the United Arab Emirates, which had asked South Korean firms to a build the country’s first nuclear power plant.

At the beginning of this year, of the 62 nuclear power plants with a combined capacity of 60 gigawatts (GW) under construction in 14 countries, 24 were located in China. The world total is down from a 25-year high of 67 in 2013.

Three quarters of the projects have been delayed, many by several years. Four EPRs under construction in Finland, France and China are years behind schedule. And, for the nuclear industry, it might still get worse.

The Chinese government stated on 27 January 2016 that following safety concerns, construction of two EPRs that a Franco-Chinese consortium is building at Taishan in Guangdong had been delayed.

Fabrication faults have been identified in the reactor pressure vessel of the EPR built at Flamanville in France. The same fabrication process has been used for the Taishan vessels.

The French nuclear safety authorities said they will take until the end of the year to decide whether the material used in the reactor pressure vessel—which are clearly below technical specifications—is acceptable from a safety point of view. The Chinese authorities’ attitude towards this issue will be under close international scrutiny.

Source: World Nuclear Industry Status Report (or simply WNISR), MSC, 2016

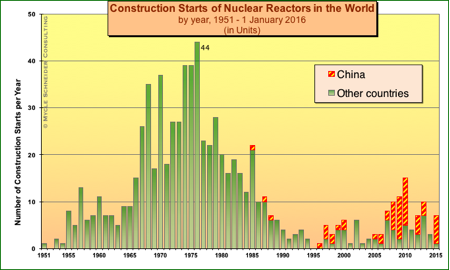

The relatively high number of grid connections in 2015 is clearly a result of decisions taken in China pre-Fukushima. In 2009, China launched seven of the nine new nuclear construction projects in the world that year, and in 2010, ten out of 15.

Since the Fukushima disaster, the number of construction starts plunged to three in 2014, of which none were in China. In fact, China has slowed the pace of reactor building.

China’s new nuclear

Between 2011–2015, China launched only three more units. Will the rhythm of reactor building pick up again? Can it be sustained over the years to come?

Officially, during 2015, the Chinese government granted permission for the building of eight more reactors, the first ones to get the go-head after a four-year freeze. These include licences for two units in Fangchenggang of south China’s Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, and a two-reactor expansion of the Tianwan nuclear power station in Lianyungang of east China’s Jiangsu province.

Construction started on one unit at each site within days of the 16 December 2015 announcement by the State Council. It’s a highly contested topic, whether nuclear power plants should be built not only in coastal areas—as are practically all of the current projects—but also inland.

China’s nuclear exports

It is also too early to say whether the build-up of expertise and competence can be accelerated to the level needed to operate, fuel and maintain a rapidly growing nuclear reactor fleet. At the same time, the Chinese nuclear industry is aspiring to expand into foreign markets.

Industrial giants China General Nuclear Power Group (CGN) and China National Nuclear Corporation (CNNC) have proposed their yet-to-be-built Hualong One, a so-called Third Generation reactor design, to Argentina, Pakistan, South Africa, the UK, and even Kenya.

It remains to be seen whether these projects can be technically implemented and proven commercially viable. After a rapid rise in the first half of 2015 on the Hong Kong stock exchange, CGN shares lost 60% of their value in six months.

Credit-rating agencies have made it clear that involvement in the Hinkley Point C project in the UK, now delayed again, is “credit negative” for CGN, CNNC and the French EDF.

“Financial catastrophe”

The association of EDF employee-shareholders (EAS) called the Hinkley Point C project “a financial catastrophe foretold” and asked the management to abandon the project. On 7 December 2015, Euronext ejected the French heavy weight Électricité de France (EDF), the largest nuclear utility in the world and “pillar of the Paris Stock Exchange”, from France’s key stock market index, known as CAC40.

Two days later, the trade union representatives at the Central Enterprise Committee of EDF—unanimously and for the first time—launched an official “economic alert procedure” considering the “seriousness of the situation”.

In the third week of 2016, EDF and Areva shares hit a historic low, a drop of 87% and 95% respectively from their values eight years ago. The French government’s January 27 decision to inject €5 billion into the bleeding Areva Group will likely only provide short-term pain relief.

While the Chinese stock-market plunge clearly played a role in the latest downward trend, it is clear that when the Chinese economy sneezes, the French nuclear industry catches a cold. That is all the more dangerous as the atomic giants were already sick.

Mycle Schneider is the lead author and publisher of the annual World Nuclear Industry Status Report.