Dubbed “China’s Love Canal”, the toxic scandal of Changzhou Foreign Languages School in east China’s Jiangsu Province hit media headlines earlier this month. Hundreds of students became sick after attending the school, which had been relocated in 2015 to a toxic waste dump used by former chemical factories.

The Changzhou case has generated public outcry. Soil and groundwater tests around the school revealed extremely hazardous toxic substances, according to a report by China Central Television.

Parents and students had suspected that pollution was the source of the illnesses, which range from rashes, headaches, coughs and nosebleeds, to cancers including lymphoma and leukemia.

Commentators have compared the Changzhou case to the infamous Love Canal environmental disaster that took place in Niagara Falls, New York, in 1978. The parallels are striking: Love Canal exposed the alarming health consequences of a toxic chemical dump buried beneath a school. Love Canal also attracted mass media attention and public outrage that such a disaster could happen.

Love Canal was a major turning point that shaped environmental policy in the US. It is widely cited as the beginning of the anti-toxics movement and was a landmark event in the grassroots struggle for compensation.

One of the most important legacies of Love Canal was the creation of the Superfund Act of 1980, through which national legislation to tax corporations to clean up hazardous waste sites throughout the US.

Environmental activists in China, too, are calling for new laws in the wake of the Changzhou disaster.

This is not the first time such a comparison has been drawn. In February 2013, the furious online reaction to a blog post about dumping and groundwater contamination in Shangdong Province was described as China’s Love Canal moment and heralded a plea in China for further action.

What was the significance of Love Canal, and why is this comparison important for China?

Love Canal

Love Canal was originally built in the 1890s by the entrepreneur William T. Love, a dream project to connect the upper and lower Niagara Rivers and power his proposed company town “Model City”. However, Love abandoned the canal after digging around 1,000 metres due to lack of funding.

Belying its popular image as a tourist destination, Niagara Falls became a hub for heavy industry in the first half of the 20th century. Chemical factories lined the banks of the river, attracted by the extraordinary natural resource of the falls and the proximity to integrated Rust Belt industries. The industrial city expanded rapidly, attracting new workers in search of factory jobs.

Between 1942 and 1953, Hooker Chemical Corporation (now part of Occidental Chemical Corporation) buried approximately 20,000 tons of toxic industrial waste into Love Canal including more than 200 chemicals. They sealed the waste with a clay cap, but did not line the canal to prevent leakage.

In 1953, Hooker Chemical sold the 16-acre site to Niagara Falls Board of Education for a nominal US$1, with the clause that it would not be held responsible for the harmful effects of the waste. In the late 1950s, an elementary school and 100 houses were built on top of the dump, and the working class community of LaSalle grew up around this area.

The new residents were not aware of the area’s toxic history, but they became suspicious when chemical liquids began erupting in their basements and backyards, following a particularly harsh winter in 1977. Already concerned about their housing values, residents became increasingly frightened – and angry – when a number of miscarriages, birth defects, and illnesses started to occur in their community.

Under the leadership of Lois Gibbs, a resident and mother, the Love Canal Homeowners Association campaigned to have the school closed and the health effects of Love Canal investigated. At first, government officials, corporate representatives, and scientific experts denied any health risks associated with living in Love Canal. However, after extensive campaigning and further reports of illnesses, Love Canal hit the national media headlines.

In August 1978, the New York health commissioner declared a state of emergency in Love Canal and 239 families were evacuated. US President Jimmy Carter subsequently announced a state of emergency, the first ever declared over a technological disaster, and funded the evacuation and relocation of 780 further families in March 1980.

[A timeline of the events at Love Canal can accessed here]

The disaster at Love Canal led to the creation of the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act (CERCLA) in 1980, commonly known as the Superfund.

The federal Superfund law taxed the chemical and petroleum industries, setting up a US$1.6 billion trust fund for cleaning up hazardous waste sites. The Superfund is managed by the US Environmental Protection Agency and has since been used to clean up hundreds of toxic sites.

Love Canal was officially removed from the Superfund list in 2004, but controversies continue about the enduring toxic legacies of the site.

Legacy

The legacy of Love Canal is decidedly mixed. It was a pivotal disaster in the history of environmental politics and legislation. Despite years of work and a great deal of expenditure, many Superfund sites remain toxic.

Corporations continue to pollute, and communities continue to suffer. In particular, environmental hazards continue to be concentrated in minority and low-income communities.

Robert Bullard, the “father of environmental justice”, has highlighted the problem of “Black Love Canals” throughout the US, where issues of environmental injustice are deeply connected with racism.

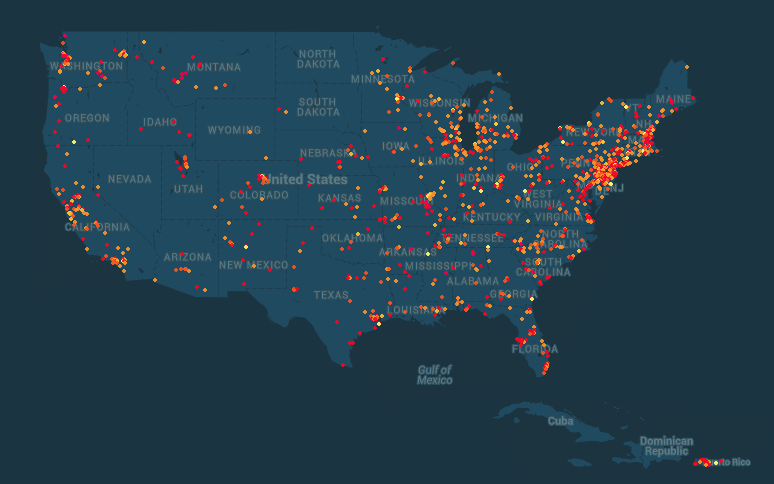

A map of toxic Superfund sites in the US created by https://www.toxicsites.us/ Please click on the map to enlarge

Race and pollution

There have been numerous cases of environmental injustice in the US, but they have not received the same national media attention as Love Canal. The case of polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB) landfill in the predominantly African American town of Warren County, North Carolina (1973-1982), and the case of DDT contamination in the predominantly African American town of Triana, Alabama (1977-1982), are commonly cited as the beginning of the environmental justice movement, with links to the civil rights movement.

The two-year water contamination crisis in Flint, Michigan has been cited as the most recent US scandal of environmental injustice. In March 2016, The Flint Water Taskforce issued a report suggesting that the majority black residents “did not enjoy the same degree of protection … provided to other communities”.

Second wave

The toxic legacy of Love Canal also continues to haunt the original site. In the 1990s, despite controversies over the lack of an environmental risk assessment, developers began to sell new homes in the former Love Canal area, rebranded as “Black Creek Village”. Residents were made aware of the chemical history, but they were attracted by prices below market value. Property agents led them to believe that the area no longer posed a risk to health.

A new wave of lawsuits over the toxic effects of Love Canal began in 2013, with residents of Black Creek Village reporting illnesses eerily reminiscent of those in 1978. The last compensation claims from the original Love Canal case were only resolved in 2005, after decades of delay, and the second wave of claimants also face long court delays.

Lingering threat

Love Canal has also migrated to haunt other places. Between 1964 and 1968, toxic waste was moved from the original Love Canal site to Wheatfield, New York and capped, with no reported leakages. However, the removal of toxic waste from the landfill in 2014 caused the site to be demoted from class three to class two. In 2015, the Wheatfield site was added to the list of Superfund sites that pose a significant threat to the community, an irony after undergoing costly remediation.

Thus, the Love Canal story continues, on multiple levels. Countless Love Canals lie in wait, yet to be discovered. Their effects are deeply uneven. Most do not receive media attention or political voice, and so they remain hidden from public view. There are multiple hazardous waste sites in the US alone, and many more around the globe.

The lessons of Love Canal for the disaster in Changzhou are sobering and urgent. There are clear parallels between the disasters. But only time will tell whether Changzhou, or other disasters, has the capacity to change the landscape of environmental politics, litigation, and history.