Li Jing, born in 1978, grew up with three pigs, chickens, and ducks on her family’s small farm in Hubei province, central China. In those days, meat was rarely on the table – a delicacy reserved only for celebrating Chinese New Year.

In high school, Li remembers her awe when chicken drumsticks began appearing on shop shelves: “that used to be such a luxury, each chicken only has two.” During China’s era of rapid economic growth in the 1990’s, meat became cheaper to buy rather than raise. Her family sold their pigs.

Now a professor of economics in China’s southern Guangdong province, Li rarely eats meat. Though low-cost meat is widely available, she is concerned about growth hormones, antibiotics, and other feed additives used in meat production. Li’s mother freezes and sends her chicken and duck meat through friends and relatives making the 1000-kilometre journey from Hubei to Guangdong.

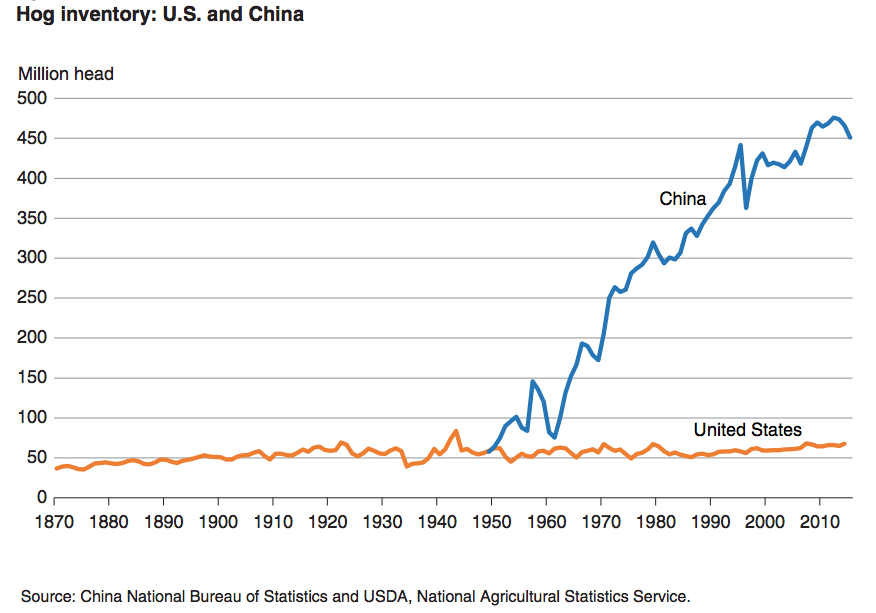

Since the start of China’s opening to the outside world and wave of new economic reforms in 1978, the country has lifted 800 million people out of poverty and succeeded in putting meat on the table. In 1978, China’s total meat consumption was one-third that of the US. Now it is double US consumption. While per person, the Chinese still only eat half as much meat as Americans, consumption is rising as China’s dietary patterns follow Western trends.

China’s agricultural system is also following in the footsteps of the West. From the purchase of US pork processor Smithfield and Dutch grain trader Nidera, to the pending takeover of Swiss pesticides and seeds group Syngenta, China is moving towards large scale industrial production. But despite benefits such as the wide availability of cheap meat in China, the new model carries hidden costs.

A small scale farm on the remote hillsides of Miyun county where Chinese black pigs roam freely (Image: Author)

Building up big industry

China’s meat industry has undergone a rapid transformation. In the place of small backyard farms, confined animal feeding operations (CAFOs), which consist of thousands or tens of thousands of animals, have become the norm.

“For both dairy and pork, there’s been a real exodus of small-scale producers over the past five years and an influx of giants ones,” says Fred Gale, a senior economist at the United States Department of Agriculture. Small backyard farms, which made up 90% of all pig farms during the 1980s, dropped to one-third of pig farms in 2012. This decline continues.

The emergence of new agricultural conglomerates like W H Group (formerly known as Shuanghui), New Hope Group, and Guangdong Wen’s Foodstuffs Group, which processed 119 million chickens and 17 million pigs in 2016, have marked this transition. Pig and poultry producers, New Hope Group and Wen’s Group, are also among the top ten largest animal feed manufacturers globally.

Chinese government policies have supported the conglomeration of the meat industry. In 2013, China’s Ministry of Commerce encouraged companies to take more control over pig production and China’s latest agricultural Five-Year Plan (2016-2020) called for enlarged hog farm sizes to boost international competitiveness.

Also, revised environmental protection laws allow local government officials to designate special zones for livestock production, forcing existing farmers in an area to shut down operations or relocate. Fujian province closed more than 14,000 small farms in the first half of 2015.

China’s shift to support larger producers and learn from Western management practices has been driven by food safety and environmental concerns. Lingering memories of the melamine milk scandal in 2008, and the 16,000 dead pigs found floating down the Huangpu River in 2013, which is a source of tap water for Shanghai, have created a shroud of mistrust over the meat and dairy industry.

In 2011 one of Shuanghui’s subsidiary pig farms was caught using an illegal feed additive that prevented accumulation of fat in pigs. The scandal spurred Shuanghui’s US$4.7 billion dollar purchase of US meat processing company Smithfield, that specialises in industrial pig-raising operations in 2013. The shift towards larger meat producers and the adoption of Western practices could provide greater quality control over the whole supply chain, access to better technology and even boost accountability over manure treatment.

Scaling-up meat production also helps Chinese companies, which are struggling to compete with international prices, trim the fat on costs. Between 2012 to 2015 the wholesale price of pork in China was double that of the US primarily due to lower labourer productivity and higher costs for animal feed. The US pork industry produced 80 times more meat per labourer – a level of productivity that China hopes to adopt too.

But while some see benefits in going large scale, others are not convinced that the Western model of industrial meat production holds the solution.

Wang Jing, who manages China’s Greenpeace Food and Agriculture team, questions the idea that bigger is better. While on the surface, regulation of larger operations may seem easier in practice, Wang points to the recent Brazil beef scandal where the country’s largest meat producers were accused of bribing health inspectors to look past food safety abuses.

Despite stringent food safety guidelines, Chinese regulators cannot always ensure implementation. “There’s no transparency,” says Wang.

Chen Naxin, who works for a Chinese chemical company in Sichuan that manufactures additives for livestock feed, also has no trust in regulatory enforcement. “When companies scale up, they don’t sell to the people, they sell to the processing company so they don’t care. To producers it’s considered a commodity, not necessarily food.”

Hidden costs

Concentrated and confined livestock production systems are controversial in the West as well. The model of producing crops for feed, purchasing feed additives, collecting, storing, and hauling manure, and providing veterinary care to keep livestock healthy under crowded conditions has hidden environmental and economic costs.

Of the over US$246 billion in US agricultural subsidies since 1995, 63% have supported the meat and dairy industry. China’s pork subsidies reportedly exceeded $22 billion in 2012 alone according to a Chatham House report.

Manure from CAFO’s in the US also contributes to elevated nitrogen and phosphorus levels in waterways, causing toxic algal blooms and the loss of wildlife, such as the decline of crabs and oysters in the Chesapeake Bay. Concerns have also been raised that cramped conditions inside CAFO’s create breeding grounds for pathogens, require higher use of antibiotics, and cause reduced air quality around industrial farms.

The industrial meat model in the West is also resource intensive: it takes two kilogrammes of feed to produce one kilogramme of chicken or pork. To produce one kilogramme of beef requires 15,000 litres of water compared to 1,250 litres for a kilogramme of maize or wheat.

“The US livestock system makes no sense ecologically,” says Ray Weil a Professor at the University of Maryland’s College of Agriculture and Natural Resources. Weil and his colleagues found that producing milk from cows through carefully managed grass-grazing practices as opposed to conventional confinement, had the potential to lessen environmental impacts while raising profits.

For China, a country that supports 20% of the world’s population on only 8% of its arable land, the resource-intensive Western meat system may not make sense.

“The meat industry would say this is a model for efficiency whereas environmental activists say this is the worst kind of model that should be exported from the US to China,” says Janet Larsen, an expert on global food supply and founder of the consulting group, One Planet Strategies.

Meanwhile, the meat model that China buys into will affect the world. Though China’s domestic meat production has become more efficient, it has declined in recent years as imports rise to satisfy growing consumption. In 2017, China is expected to overtake the US as the top importer of chicken, pork, and beef. Already, China is the world’s largest buyer of soy beans for livestock feed, the leading cause of global deforestation.

If the Chinese consumed as much meat as Americans under the current Western industrial system, says Larsen, we would not have any forests.

A sustainable model

But a new pool of farmers is emerging in response to China’s food scandals and increasingly industrialised agricultural system.

Small local producers have sprung up in China, many of which draw on more sustainable traditional practices of integrated livestock husbandry alongside crop rotations and nutrient recycling.

“We have a great history of ecological farming and management that we should support,” says Wang, who hopes that Chinese government policy will champion more ecological agricultural production.

There is growing interest in farmers markets, community supported agriculture (CSA) models, knowing your farmer, and an e-commerce market for organics in China’s major cities.

Chen has observed a rise in the demand for pork from traditional Chinese black pigs. However, he admits the majority of Chinese are choosing lower prices and the convenience of processed meat that comes from the Western pig varieties that China produces and imports at scale.

In the US, consumers have also been driving new industry trends. Currently, the demand for grass-fed products in the US outstrips supply and farmers are increasingly looking to make the switch. Meanwhile, America’s latest nutrition trends call for reduced meat consumption and more vegetables.

A leading advocate for diets as a way to cure America’s chronic disease epidemics, Michael Pollen, calls on consumers to: “Eat food. Not too much. Mostly plants.” CEO of Whole Foods, John Mackey, recommends that no more than 10 percent of calories come from grass-fed animal protein and points to Eastern dietary traditions where plant-based diets correlate with longer life expectancies.

Since 1978, China has come a long way on its modernising path. But it remains to be seen whether the country will follow in the footsteps of the West or learn from the drawbacks of industrial meat practices and adopt a more sustainable system.