The Yellow River today is China’s environment in miniature. At the source on the Qinghai-Tibetan plateau, it is affected by climate change; the middle reaches are dried-up because of over-development, and suffer water shortages; and the lower reaches and estuary are dotted with chemical plants dumping untreated, polluted effluent directly into its waters.

The Yellow River stretches almost 5,500 kilometres, running from west to east through China’s northern provinces. It is seen by many Chinese as the “mother river” because in ancient times its alluvial plains nurtured the Huaxia, the tribes from which Han Chinese trace their ancestry.

The river is now desperately short of water. In addition to providing for agriculture, it must also meet the needs of industry, which returns polluted water back to the river.

Since 2010 Wang Yongchen, an environmentalist and senior reporter with China National Radio, has been organising long-distance journeys following the Yellow River upstream. Her aim is to witness, record and expose the environmental crises unfolding along the river’s banks. She is accompanied on these journeys by environmental volunteers and journalists.

Wang has made the trip annually for the past eight years and will continue for two more. She starts where the Yellow River meets the sea in the coastal industrial city of Dongying and makes her way to its source on the Qinghai-Tibetan plateau, recording how the river changes each year, particularly, how polluted it is.

Wang’s journey has coincided with environmental protection moving from the margins of Chinese politics and society into the mainstream. In 2013 and 2015 specific laws tackling air pollution and water pollution came into force. A process to establish ten national parks was started in 2015. In 2018 the Ministry of Environmental Protection was upgraded to the Ministry of Ecological and Environmental Protection and given a wider jurisdiction.

Will those changes trickle down and have a positive impact on the Yellow River? Three entries from Wang’s 2017 travelogue record some of the hard-won changes she has witnessed.

The Decade of Yellow River Journeys project hopes to record the changes inflicted upon the river by climate change and our thirst for wealth. And, of course, I hope this process will have an impact: more openness of information, more public participation, and more social progress.

We set off from Beijing in the early morning of August 16, 2017, and travelled to Dongying in Shandong province, where the Yellow River meets the sea. From there we started our trip up the river, to its source in Yueguzongli, Qinghai. It is the eighth year of our decade.

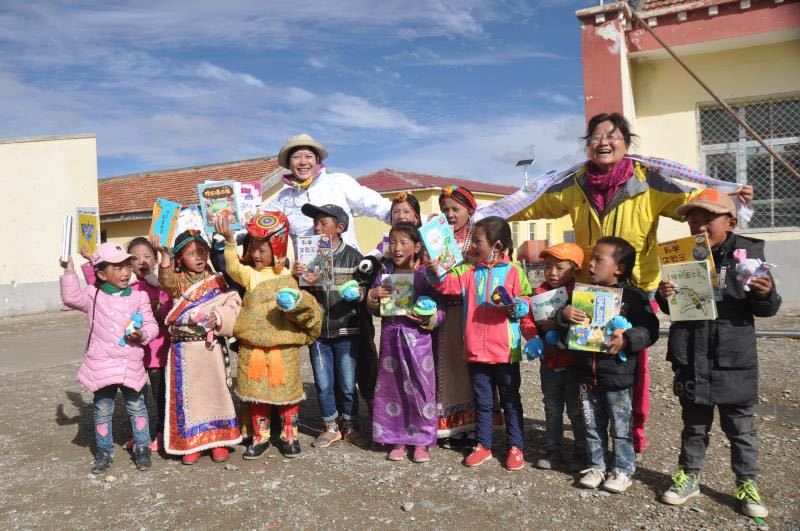

Wang Yongchen (second right) and students from an elementary school at a source of the Yellow River (Image: Wang Yongchen, 2017)

The Yellow River Delta

August 16, 2017

The Yellow River is named for its muddy waters. In 1958, 2.1 billion tonnes of silt flowed into the sea, and about 30 square kilometres of land were created here every year.

On its trip of thousands of kilometres from Qinghai, the Yellow River collects huge quantities of silt, trace elements, diatoms (a major group of microalgae) and nutrients. These get deposited in the Yellow River delta. Today, an area of 153,000 hectares is protected here for its natural, geological and scenic importance. The delta is one of thirteen wetlands given international protection.

In an interview with researchers from the Yellow River Estuary Nature Reserve, we learned that the reserve is home to 800 aquatic species and various rare and endangered birds, including “Schedule 1” protected species such as the red-crowned crane and golden eagle. The Saunder’s gull, endangered worldwide, is also found here.

But the formation of land by the deposition of silt has created opportunities for oil drilling. The Shengli oil field, first drilled in the 1960s, is the most intensively exploited of China’s oil fields, and has attracted many chemical firms to set up nearby. Since 2010 we have seen these firms build new facilities, with the nature reserve being shrunk to make room.

But since 2013, the migratory birds that travel between the Arctic and Australia have opted to avoid the wetlands of Fujian, Jiangsu and the Yellow River estuary on their return trips north, heading instead for the islands of southern Japan.

Scientists blamed this new phenomena on land reclamation in the Yellow River estuary. Wetlands were dried out and covered with fish farms, causing coastal species to lose their habitat. Numbers fell, leaving migratory birds short of food.

The locals blame pollution. Dongying’s expansive wetlands are now home to chemical plants. A foul smell covers the entire port in the evenings and on windy days. You can smell it dozens of kilometres away.

But there have been positive changes over the eight years. In 2014 and 2015, travellers saw black effluent being piped directly into tributaries of the Yellow River. In 2016, Southern Weekly journalist Wang Yishu wanted to do an exposé only to find that the effluent was much cleaner than before thanks to the combined efforts of government and the oil company.

In 2017, boundary markers for the reserve that had been removed were restored and firms that had breached regulations were being shifted out of the reserve.

The nature reserve was in the ascendant and the polluting factories were on their way out. There is hope that the Yellow River estuary, home to coastal wildlife and birds, will slowly recover.

The Tengger Desert

August 22, 2017

The Tengger Desert lies on the middle reaches of the Yellow River, where Inner Mongolia meets Ningxia. Under its sands lie aquifers. The local herders once showed us how they could get water from a well less than two metres deep.

But coal is mined nearby – and the combination of coal, water and a remote desert were perfect for the coal-chemical industry. Two industrial zones were built in the heart of the desert, attracting chemical firms.

When our group arrived here in 2011 they were met by a local herder, who had learned of their trip online and waited seven hours for them. He wanted to take them to his home, where 32 chemical firms were dumping effluent directly onto the desert sands. He hoped to make more people aware of this illegal behaviour.

On our fourth visit here in 2014, we carefully recorded what we saw: dozens of wells over a hundred metres deep sucking up precious groundwater; several evaporation pits the size of football pitches full of dark water and sludge, giving off an offensive chemical odour. The chemical plants barely had any water treatment facilities, as “treatment” meant waiting for the water to evaporate and then transporting the sludge elsewhere.

Beijing News reporter Chen Jie published a story and photos on September 6 of that year. Later that month Xi Jinping called for pollution of the Tengger Desert to be firmly dealt with.

Eventually, 24 local officials were punished, and the offending companies forced to halt operations while changes were made. And as the herder had hoped, everyone in China knew about the pollution of the Tengger Desert.

What we didn’t expect was that when we returned in August 2016, two of our party would find themselves vomiting from foul odours. The polluters had used sand to cover the pits they were dumping effluent in but when the sand blew way the toxic sludge was exposed again.

We returned in 2017. The pits were covered with sand again, and there was some vegetation growing nearby. Participant Li Min of the Yellow River Commission identified these small trees as artificially planted desert artemisia.

The sludge pits were covered with sand again, and there was some vegetation growing nearby. (Image: Wang Yongchen)

Yueguzongli, the Yellow River’s source

September 1, 2017

The Yellow River has a number of sources, all small rivers flowing through the alpine meadows in the east of the Qinghai-Tibetan plateau. Every year, our party visits one of these on the Yueguzongli grassland, and every year we are looked after by Ouya, a teacher from the local elementary school. In the evening of August 30, 2017, Ouya’s son, Rigzin Dorje, again came to meet us in Qumarlêb county.

Dorje is a graduate of the Northwest University for Nationalities where he studied Tibetan and Chinese language and literature. On graduating, he and five classmates set up a non-governmental organisation here working on waste recycling and education called the Sprouting Grain Association.

He told us that in the past there wasn’t much domestic waste here, but as living standards improved, the locals started to produce more.

“We thought there was a huge need for environmental protections in the Sanjiangyuan region,” he said.

So today six people who grew up here are making their dreams come true. Initially, their parents were strongly opposed to the idea. One member’s father refused to speak to him for three months. But, Dorje said, his mother Ouya was supportive from the start.

Alongside the waste disposal they also now run a cooperative, mainly raising livestock and producing meat and dairy products. This gives them an income they can use to protect the river’s source.

It was very late when we arrived, but Dorje still arranged for an employee with the Sanjiangyuan National Park to come and talk to us about their work. We were excited to learn that the park is no longer fenced in, with people coming to realise that fences can be fatal for wildlife.

When we interviewed Wu Yuhu, a scientist with the Chinese Academy of Sciences’ Northwest Institute of Plateau Biology, during our first trip, he told us that, “I’d just love to tear every fence on the plateau down overnight, they create far too many obstacles to wildlife.” And over the years we’ve seen Tibetan gazelles strangled in the wires, and even yaks and horses.

But there’s a bigger crisis facing the Qinghai-Tibetan plateau, where Yueguzongli lies. This is a vast, high-altitude wetland, and as such its fate is tied up with global climate change and changes to precipitation. If rainfall increases or decreases in any one year, the grasslands are immediately affected. More rain means lusher vegetation; less rain sees it wither. And the wildlife that relies on that vegetation is affected too.

In 2013, Wang’s team interviewed glaciologist Shen Yongping, who explained that the permafrost acts like a barrier, keeping rainfall near the surface where it can flow and irrigate wetlands and grasslands. But global warming is melting the permafrost, groundwater levels are falling and this will degrade the wetlands and grasslands.

The delicate environment of the Qinghai-Tibetan plateau is particularly vulnerable to climate change: temperatures increase here twice as fast as the global average. In 2000, scientists found that rising temperatures were affecting the permafrost 15 metres down, those effects are now being seen as deep as 40 metres.

“The permafrost of the plateau has been formed over millennia. Our lifetimes, even the lifetimes of our descendants, won’t be enough to repair it,” says Shen Yongping.

“The melting of the permafrost means the Qinghai-Tibetan plateau, known as the water tower of the world, will lose water faster. What does that mean for the three billion people downstream in central and southern Asia?” he asks.